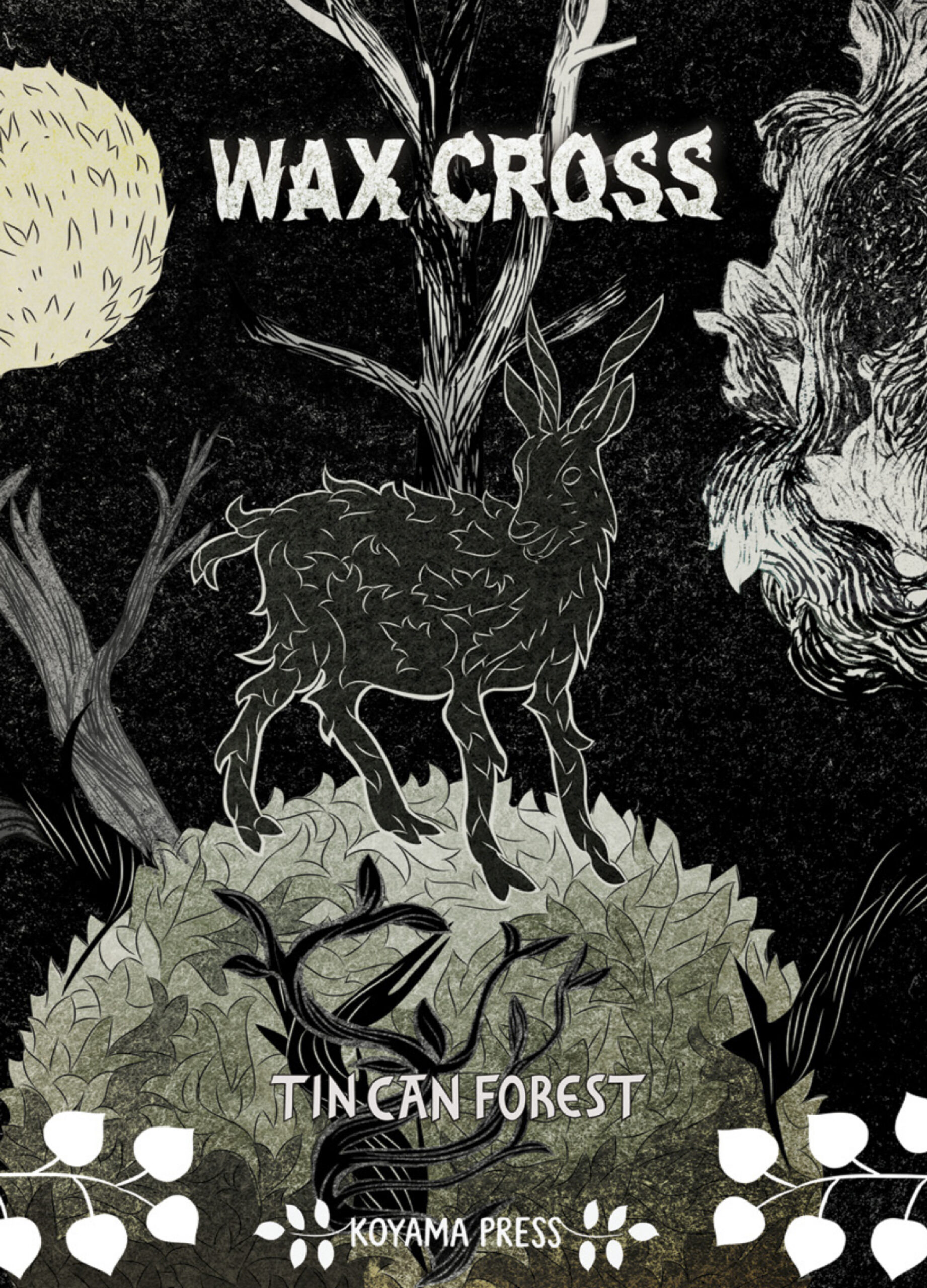

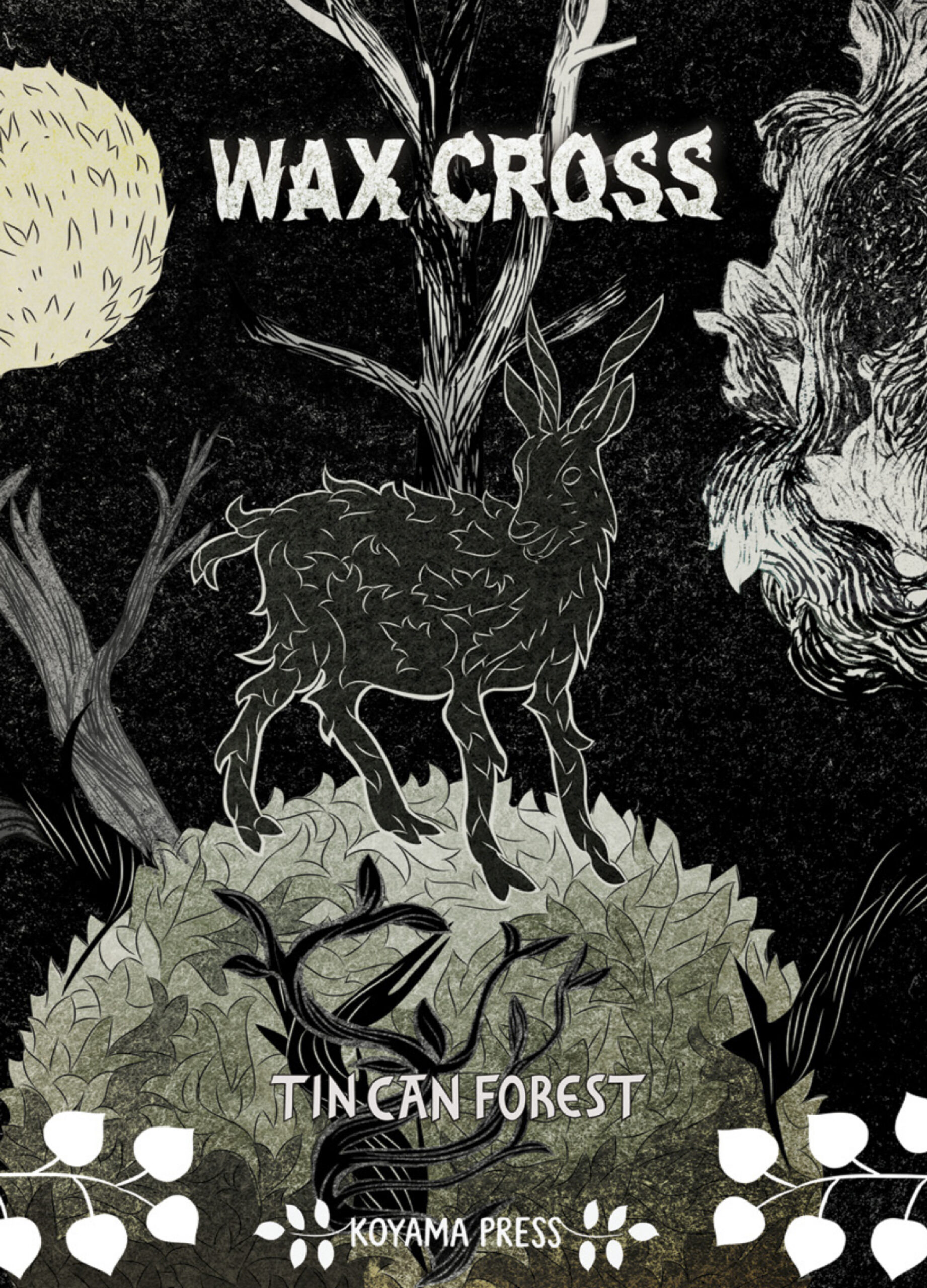

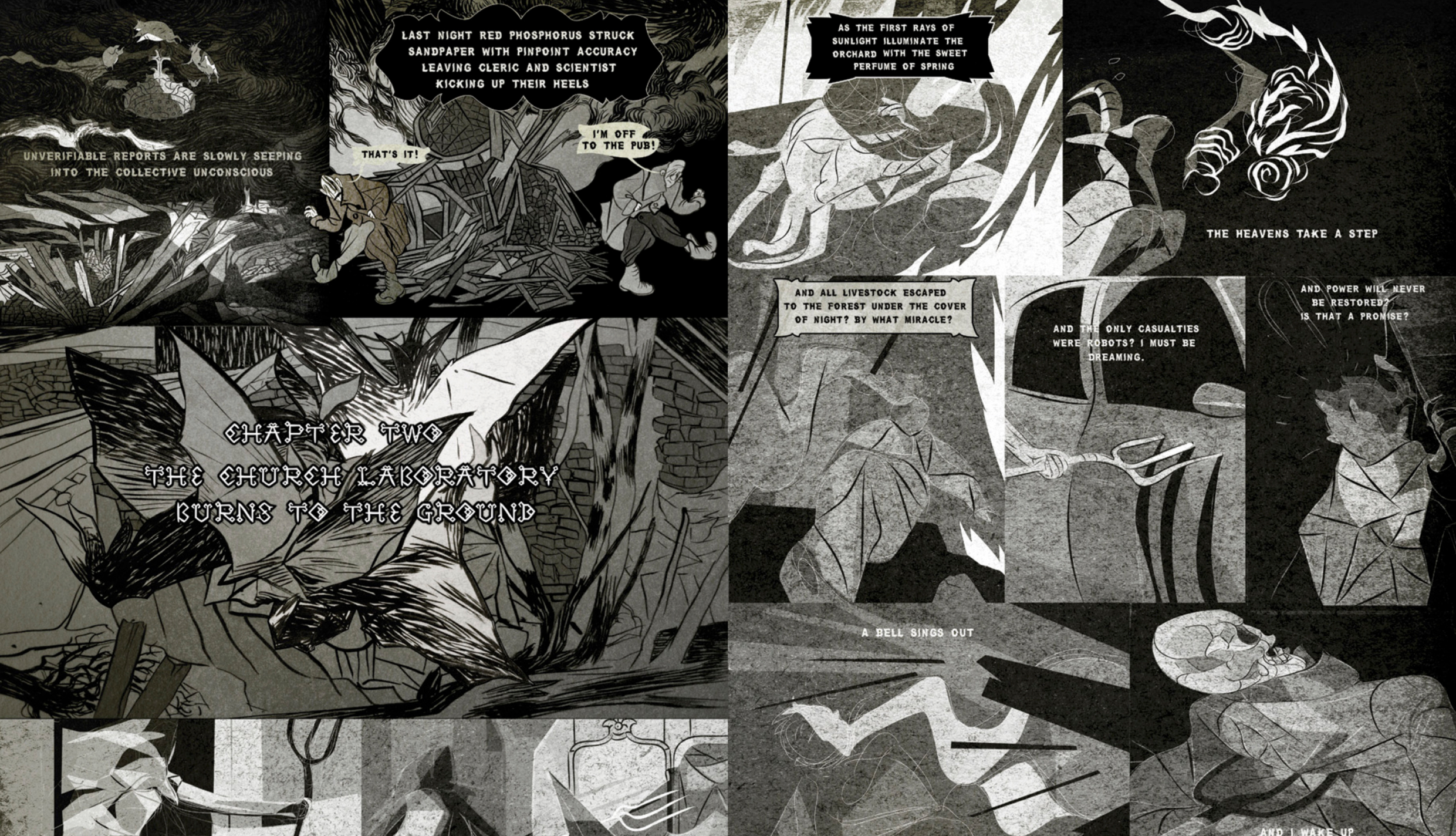

Structured as a series of linked episodes, the book reads more like a poem in chapters. Tin Can Forest (a.k.a Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek) repurpose the visual vernacular of Eastern European folklore to spin a meditation on our severed connection to the natural world. Set in “the twilight of the modern age”

– an incantation carried on the wind sets off a chain of encounters between men, women, spirits and demons.

The book, published by Toronto’s Koyama Press, is beautifully designed, and the large format really does justice to the art.

Just like the forest at the heart of its story, Wax Cross is a dense and mysterious tangle of ideas and emotions, bouncing form devilish mirth to melancholy. The haunting poetry of its pages stays with you long after you read it.

We loved the poetic, non-linear, dreamlike approach to storytelling in this book. How did you go about putting it all together? Did the art come before the words? Was the story planned from the beginning, or did it develop naturally, more organically?

Tin Can Forest: We started Wax Cross in the winter of 2010, and the first draft was entirely in black and white /grayscale, and all the text was in the style of the incantations that now appear in the spiral on page two of the book. When spring arrived, the black and white version vanished and we began to work in colour. We produced the colour spreads from late summer through autumn. When winter re-arrived, the first version re-emerged from the furthest recesses of our paper shelves and hard drives. The final edit is the combination of the two seasonal sessions.

The governing principal of our process is always collage, but with artwork that we ourselves create rather than found imagery. We work on the art and text concurrently, and neither is subordinate to the other, more a kind of counterpoint, sometime harmonious, sometimes (intentionally) dissonant. Many of the themes explored in the book were there at the inception, but we always incorporate experiences, influences, remembered dreams, and so on, that have an impact on us during the time we’re building of the book.

In terms of the art and design there’s a noticeable shift stylistically from chapter to chapter. For us it felt like the shift of mood/scene in a sequence of dreams. Was this your intention, or was it more about creative exploration?

TCF: It was definitely intentional. We wanted the chapters to be something like different songs on album, so you could listen to/read the whole thing consecutively or listen to different cuts individually. It’s not exclusively a linear, cover to cover structure. Hopefully it stands up to repeated plays.

We ended up reading Wax Cross maybe 4 times, each time picking up on a new detail or connection between characters from chapter to chapter. We sensed many of the allusions to eastern European myth and folklore (especially about demons, vampires, werewolves, and witches). Without spoiling too much of the mystery, can you help us understand the meaning of the title Wax Cross. Also, why many of the characters have a single bare foot (something we’re really itching to know)?

TCF: The name Wax Cross is a metaphor for the phenomena of dual belief ; identifying as Christian publicly and yet holding to an animistic world view as well.

More specifically, Wax Cross refers to faith in the powers of Beeswax poured during healing ceremonies in rural Saskatchewan and Alberta by descendants of Ukrainian settlers. The incantations that are recited during this ceremony refer to both Christian as well as Pagan imagery and sacred numbers. These rituals, practised primarily by women, have their roots in a European pre-Christian, Matriarchal Shamanism. This also relates to other themes in the book, such as the Witch Trials and the sanctity of bees.

About the lost shoe… well, that originates with the way devils are depicted in Czech fairy-tales, one foot in shoe, the other a cloven hoof. A long time ago, I started extending that to other characters I drew. I like the asymmetry of it, one bare foot implies a certain vulnerability, or perhaps a character was a devil in another incarnation, and a missing shoe gives them away

To us the subtext of the story felt like a lament for the loss and destruction of the natural world. Can you tell us a bit of how you approached expressing these very current concerns in the language of more traditional folklore?

TCF: At its core, traditional folklore is essentially describing phenomena in the natural world, the change of seasons, the phases of the moon, the unique qualities of different animals and plants. Pat and I are very influenced by Ukrainian Poetic Cinema, directors such as Yuri Ilyenko and Sergei Paradzhanov. These artists used visually rich folkloric imagery, and folk symbology to create polysemic narratives that spoke of landscape and national identity under a repressive Soviet state.

To me, science and statistics, even when used by well intentioned ecologists and environmentalists, abstracts our genuine experience and relationship with nature and animals. Folklore returns the power, mystery, and divinity to animals, plants, and other natural phenomena. I feel that a folkloric perspective has profound, even revolutionary implications in the context of contemporary ecological discourse.

The epilogue shows nothing but a wild tangled growth of trees, followed by what looks like a scene of cremation. Is this an optimistic ending?

TCF: Ha Ha! It is! Or maybe it’s a surprise ending. I actually just recently made a conscious decision to be an optimist about the state of the ecology. No small feat, and most likely it’s just wishful thinking. But after years of following the doom and gloom, I’m tired of being in a constant state of alarm and despair.

The drawing that you refer to as the cremation was done on our last trip to the West Coast, where we’ve just returned. My studio window looks onto a wall of fir trees, their thick, heavy branches fill the entire view. Nature is sanity. As someone wise once said: ” History ends in green.”

Thanks to you both for the interview and especially for such a thoughtful reading of our book.

S&TM: Many thanks to Pat and Marek for making such a beautiful book, and taking the time to do this interview!