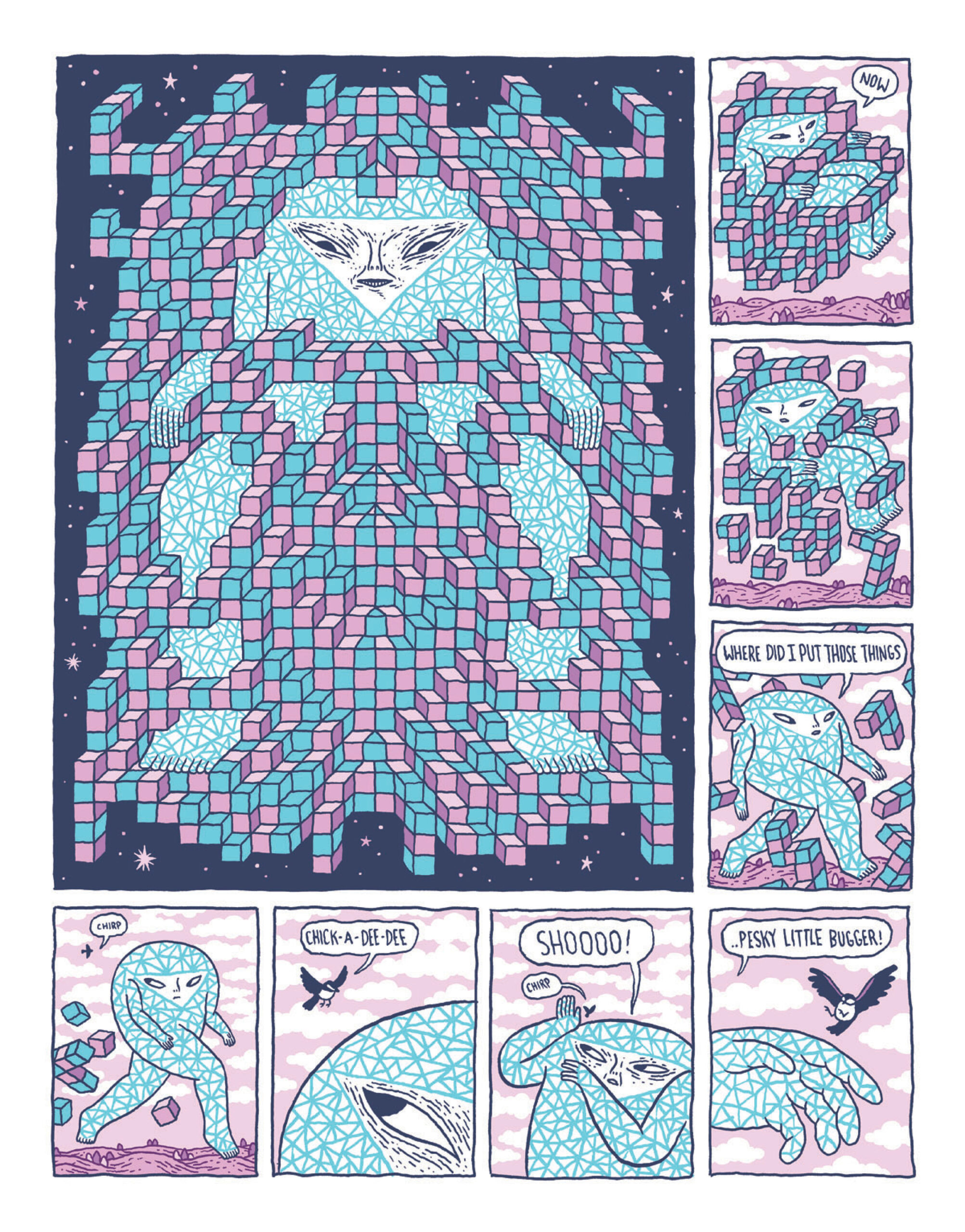

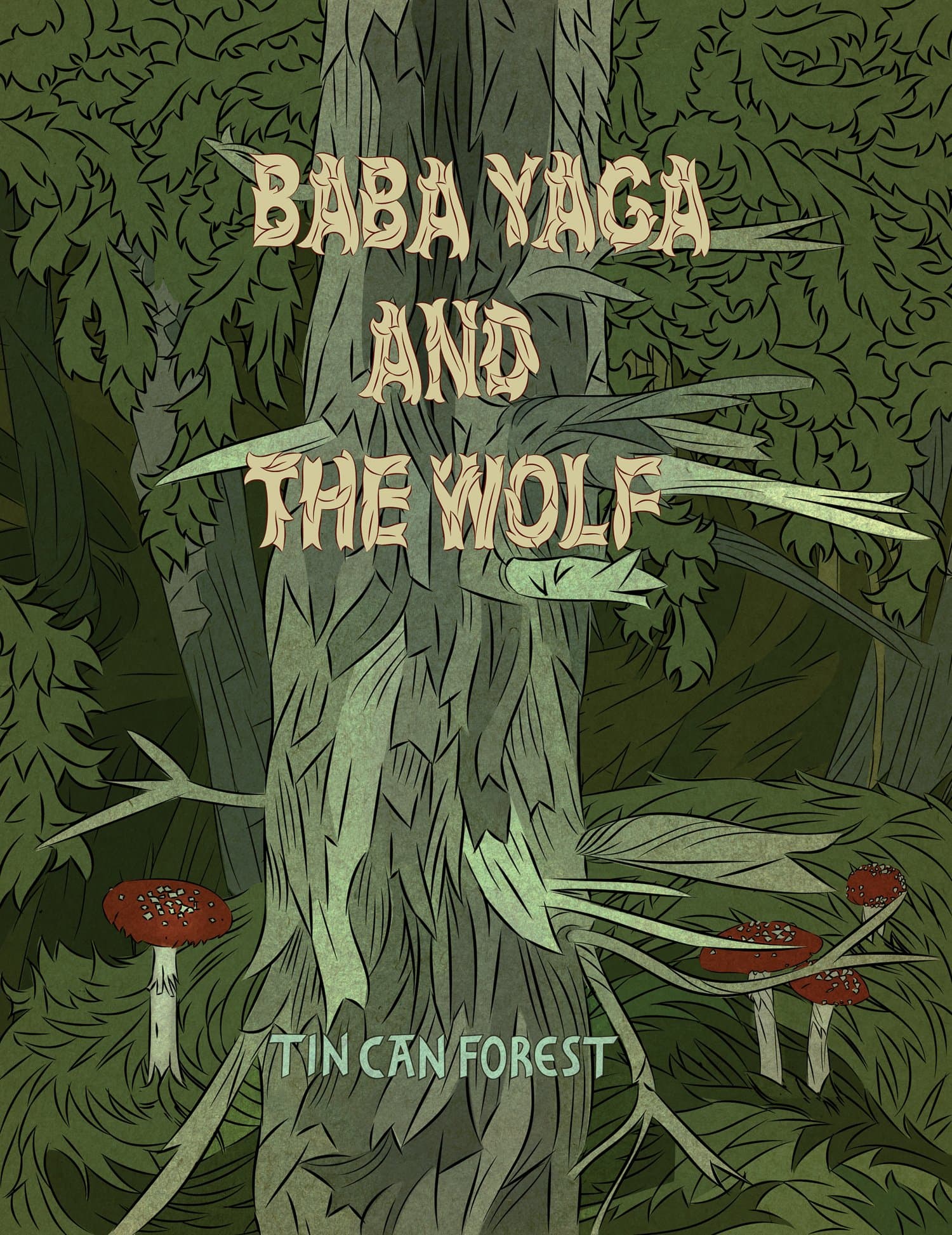

It’s been almost fourteen years since Tin Can Forest’s book Baba Yaga and the Wolf submerged readers into a dream-logic-driven tale rooted in Slavonic folklore.

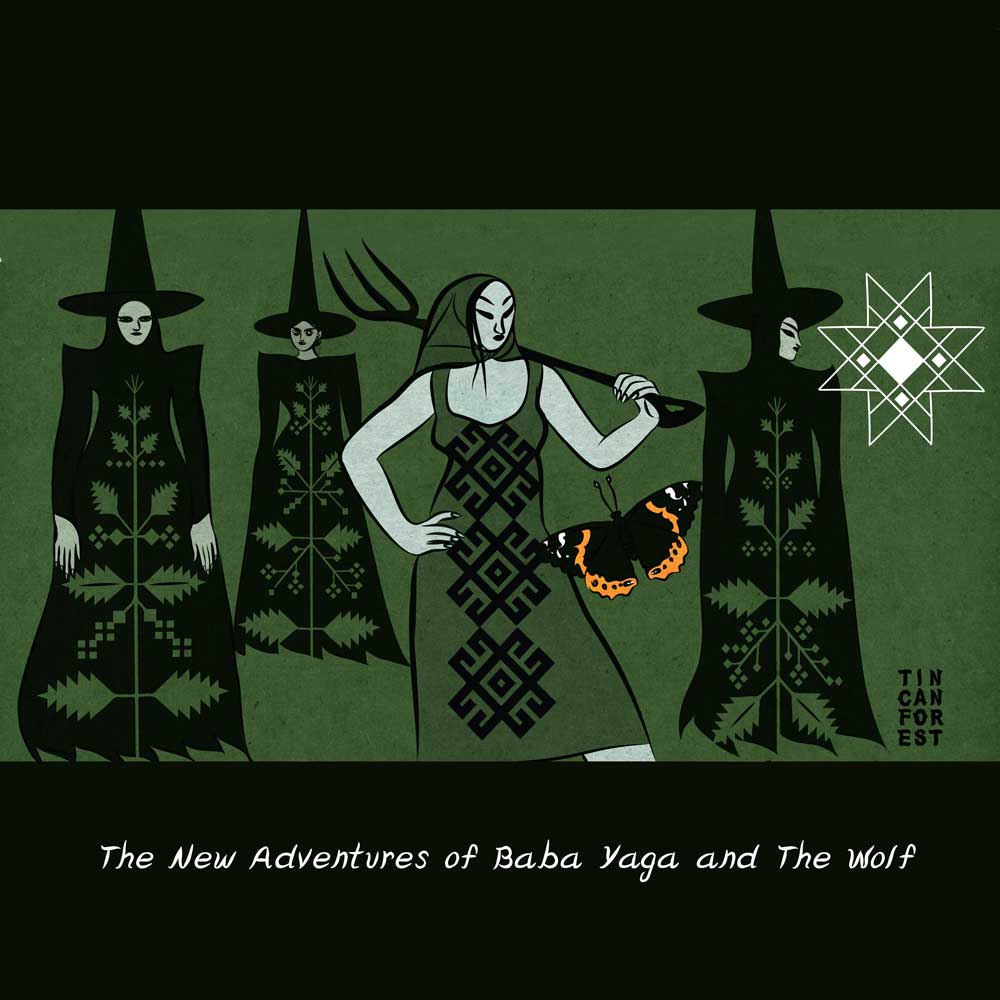

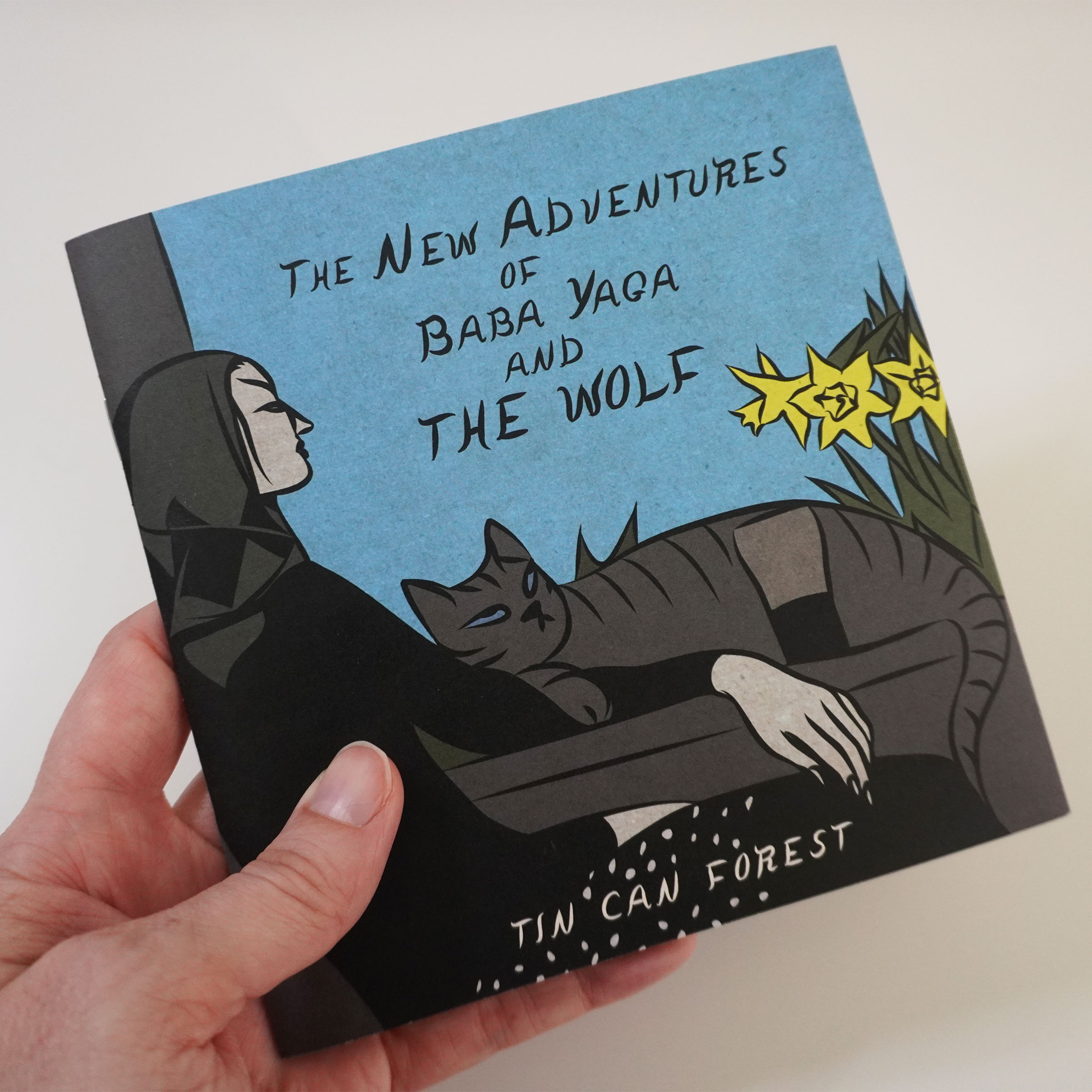

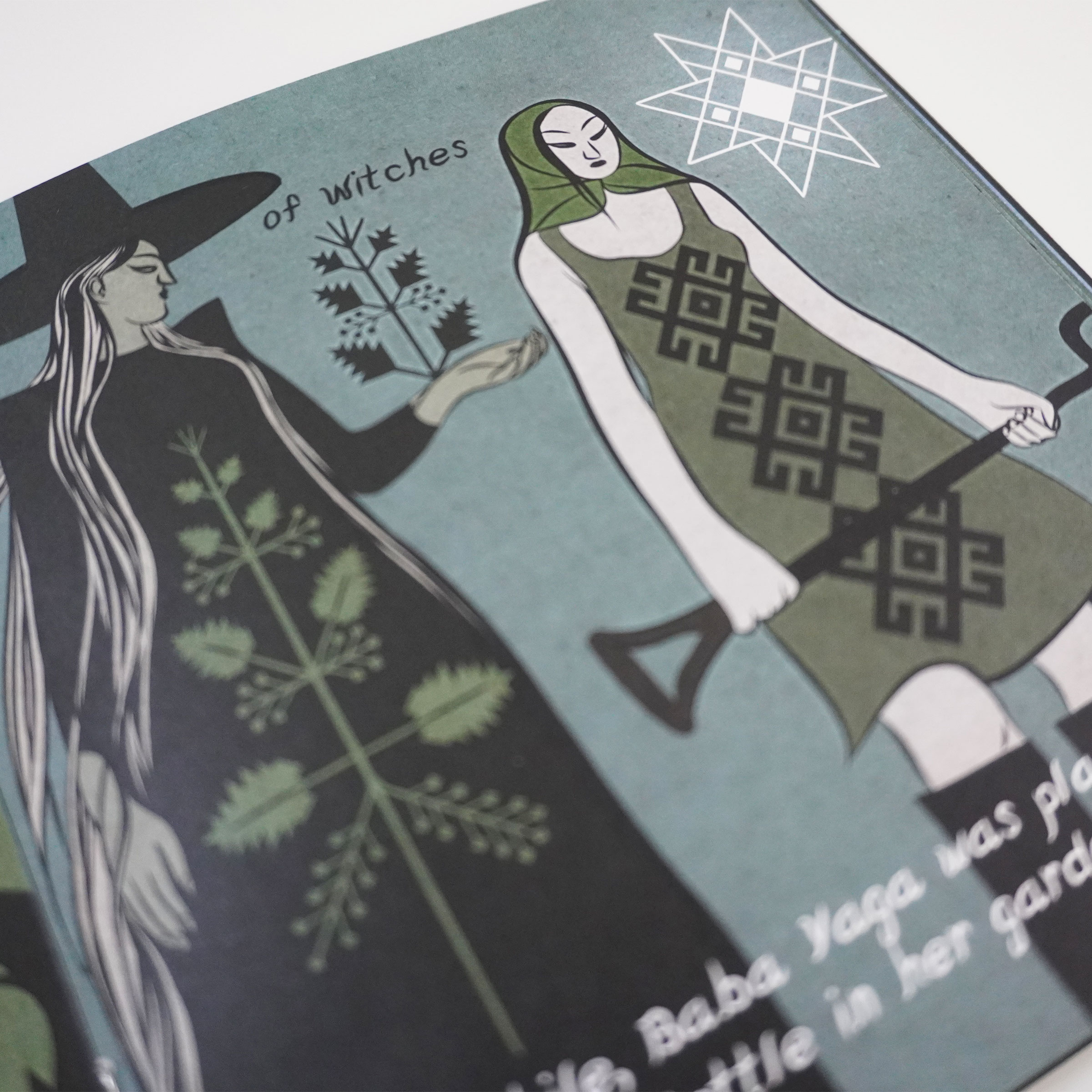

The newly published The New Adventures of Baba Yaga and the Wolf peeks into a meditative day-in-the-life of Baba Yaga as she cultivates stinging nettle in the company of demon and witch neighbours.

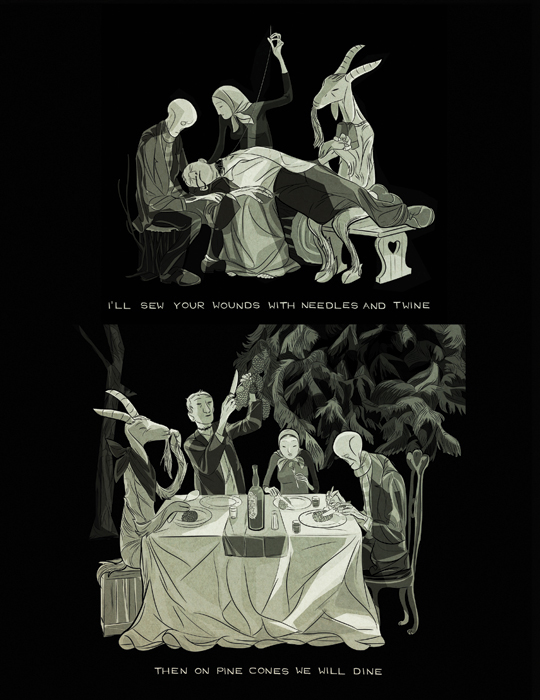

The beautifully printed limited edition comic’s small square format and accordion fold cover feel like a sly Wiccan riff on a book of hours. Artists Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek’s blend of poetic narrative, character drawings, intricate symbol and pattern design are both deeply layered in meaning, while keeping a loose punk-rock on a Sunday morning feeling. If Samuel Beckett dropped acid over brunch with soviet cartoonists, Gogol Bordello and several witches you might walk away with a similar vibe to The New Adventures of Baba Yaga and the Wolf.

This is Tin Can Forest’s seventh book after Pohadky (Drawn & Quarterly 2008), Baba Yaga and the Wolf (2010 Toyama Press), Wax Cross (2012 Toyama Press), Cabbage in a Nutshell (2014 Tin Can Forest Press), We Are Going To Bremen To Be Musicians (with Geoff Berner, 2015 Tin Can Forest Press), and What Is A Witch (with Pam Grossman, 2016 Tin Can Forest Press).

Check out their art and books at tincanforest.com and join the community at the Tin Can Forest’s Patreon.

Also, check out our past interviews with Tin Can Forest:

Wax Cross Book Review & Interview (2013)

Tin Can Forest Interview (2010)

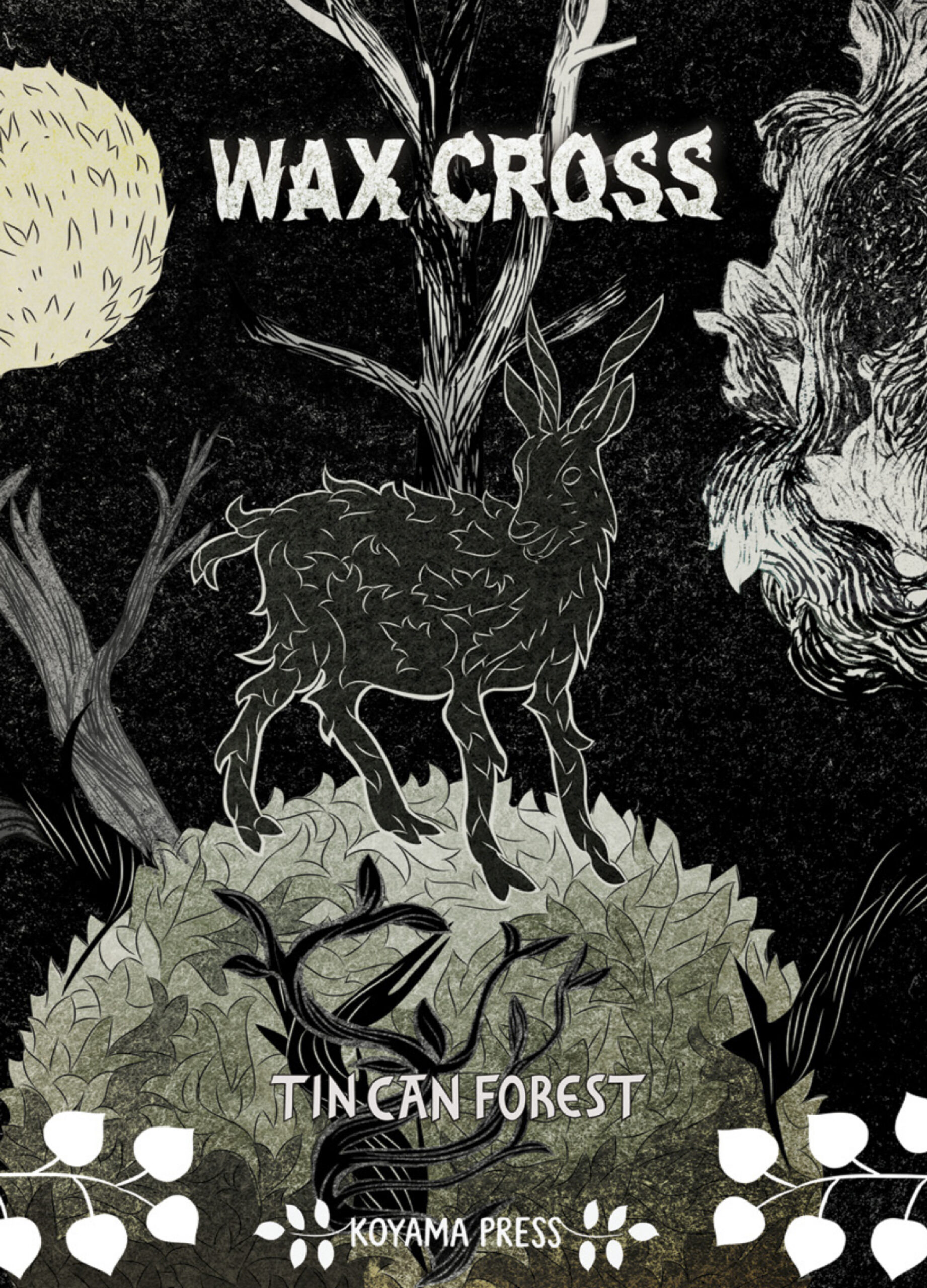

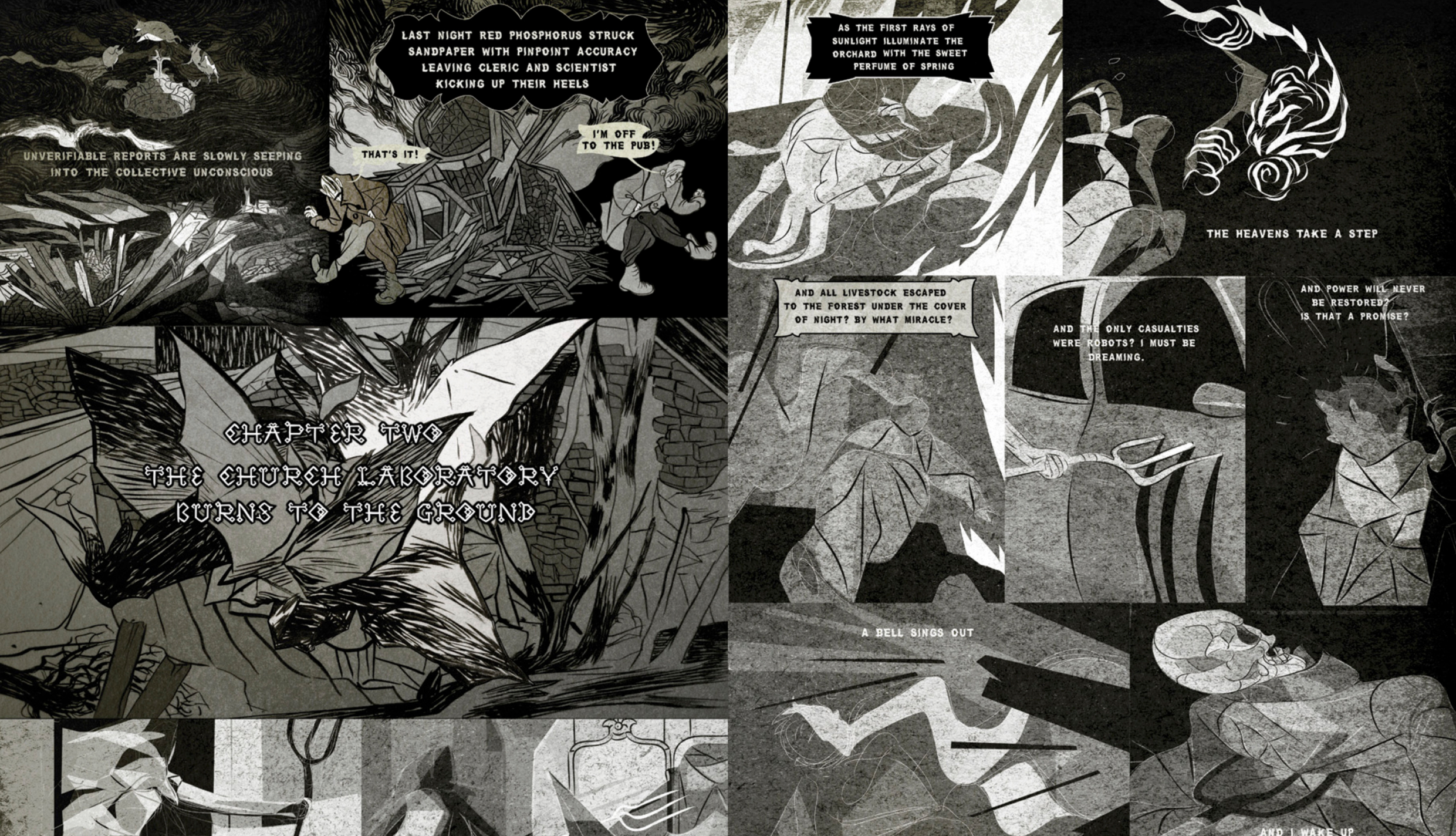

Structured as a series of linked episodes, the book reads more like a poem in chapters. Tin Can Forest (a.k.a Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek) repurpose the visual vernacular of Eastern European folklore to spin a meditation on our severed connection to the natural world. Set in “the twilight of the modern age”

– an incantation carried on the wind sets off a chain of encounters between men, women, spirits and demons.

The book, published by Toronto’s Koyama Press, is beautifully designed, and the large format really does justice to the art.

Just like the forest at the heart of its story, Wax Cross is a dense and mysterious tangle of ideas and emotions, bouncing form devilish mirth to melancholy. The haunting poetry of its pages stays with you long after you read it.

We loved the poetic, non-linear, dreamlike approach to storytelling in this book. How did you go about putting it all together? Did the art come before the words? Was the story planned from the beginning, or did it develop naturally, more organically?

Tin Can Forest: We started Wax Cross in the winter of 2010, and the first draft was entirely in black and white /grayscale, and all the text was in the style of the incantations that now appear in the spiral on page two of the book. When spring arrived, the black and white version vanished and we began to work in colour. We produced the colour spreads from late summer through autumn. When winter re-arrived, the first version re-emerged from the furthest recesses of our paper shelves and hard drives. The final edit is the combination of the two seasonal sessions.

The governing principal of our process is always collage, but with artwork that we ourselves create rather than found imagery. We work on the art and text concurrently, and neither is subordinate to the other, more a kind of counterpoint, sometime harmonious, sometimes (intentionally) dissonant. Many of the themes explored in the book were there at the inception, but we always incorporate experiences, influences, remembered dreams, and so on, that have an impact on us during the time we’re building of the book.

In terms of the art and design there’s a noticeable shift stylistically from chapter to chapter. For us it felt like the shift of mood/scene in a sequence of dreams. Was this your intention, or was it more about creative exploration?

TCF: It was definitely intentional. We wanted the chapters to be something like different songs on album, so you could listen to/read the whole thing consecutively or listen to different cuts individually. It’s not exclusively a linear, cover to cover structure. Hopefully it stands up to repeated plays.

We ended up reading Wax Cross maybe 4 times, each time picking up on a new detail or connection between characters from chapter to chapter. We sensed many of the allusions to eastern European myth and folklore (especially about demons, vampires, werewolves, and witches). Without spoiling too much of the mystery, can you help us understand the meaning of the title Wax Cross. Also, why many of the characters have a single bare foot (something we’re really itching to know)?

TCF: The name Wax Cross is a metaphor for the phenomena of dual belief ; identifying as Christian publicly and yet holding to an animistic world view as well.

More specifically, Wax Cross refers to faith in the powers of Beeswax poured during healing ceremonies in rural Saskatchewan and Alberta by descendants of Ukrainian settlers. The incantations that are recited during this ceremony refer to both Christian as well as Pagan imagery and sacred numbers. These rituals, practised primarily by women, have their roots in a European pre-Christian, Matriarchal Shamanism. This also relates to other themes in the book, such as the Witch Trials and the sanctity of bees.

About the lost shoe… well, that originates with the way devils are depicted in Czech fairy-tales, one foot in shoe, the other a cloven hoof. A long time ago, I started extending that to other characters I drew. I like the asymmetry of it, one bare foot implies a certain vulnerability, or perhaps a character was a devil in another incarnation, and a missing shoe gives them away

To us the subtext of the story felt like a lament for the loss and destruction of the natural world. Can you tell us a bit of how you approached expressing these very current concerns in the language of more traditional folklore?

TCF: At its core, traditional folklore is essentially describing phenomena in the natural world, the change of seasons, the phases of the moon, the unique qualities of different animals and plants. Pat and I are very influenced by Ukrainian Poetic Cinema, directors such as Yuri Ilyenko and Sergei Paradzhanov. These artists used visually rich folkloric imagery, and folk symbology to create polysemic narratives that spoke of landscape and national identity under a repressive Soviet state.

To me, science and statistics, even when used by well intentioned ecologists and environmentalists, abstracts our genuine experience and relationship with nature and animals. Folklore returns the power, mystery, and divinity to animals, plants, and other natural phenomena. I feel that a folkloric perspective has profound, even revolutionary implications in the context of contemporary ecological discourse.

The epilogue shows nothing but a wild tangled growth of trees, followed by what looks like a scene of cremation. Is this an optimistic ending?

TCF: Ha Ha! It is! Or maybe it’s a surprise ending. I actually just recently made a conscious decision to be an optimist about the state of the ecology. No small feat, and most likely it’s just wishful thinking. But after years of following the doom and gloom, I’m tired of being in a constant state of alarm and despair.

The drawing that you refer to as the cremation was done on our last trip to the West Coast, where we’ve just returned. My studio window looks onto a wall of fir trees, their thick, heavy branches fill the entire view. Nature is sanity. As someone wise once said: ” History ends in green.”

Thanks to you both for the interview and especially for such a thoughtful reading of our book.

S&TM: Many thanks to Pat and Marek for making such a beautiful book, and taking the time to do this interview!

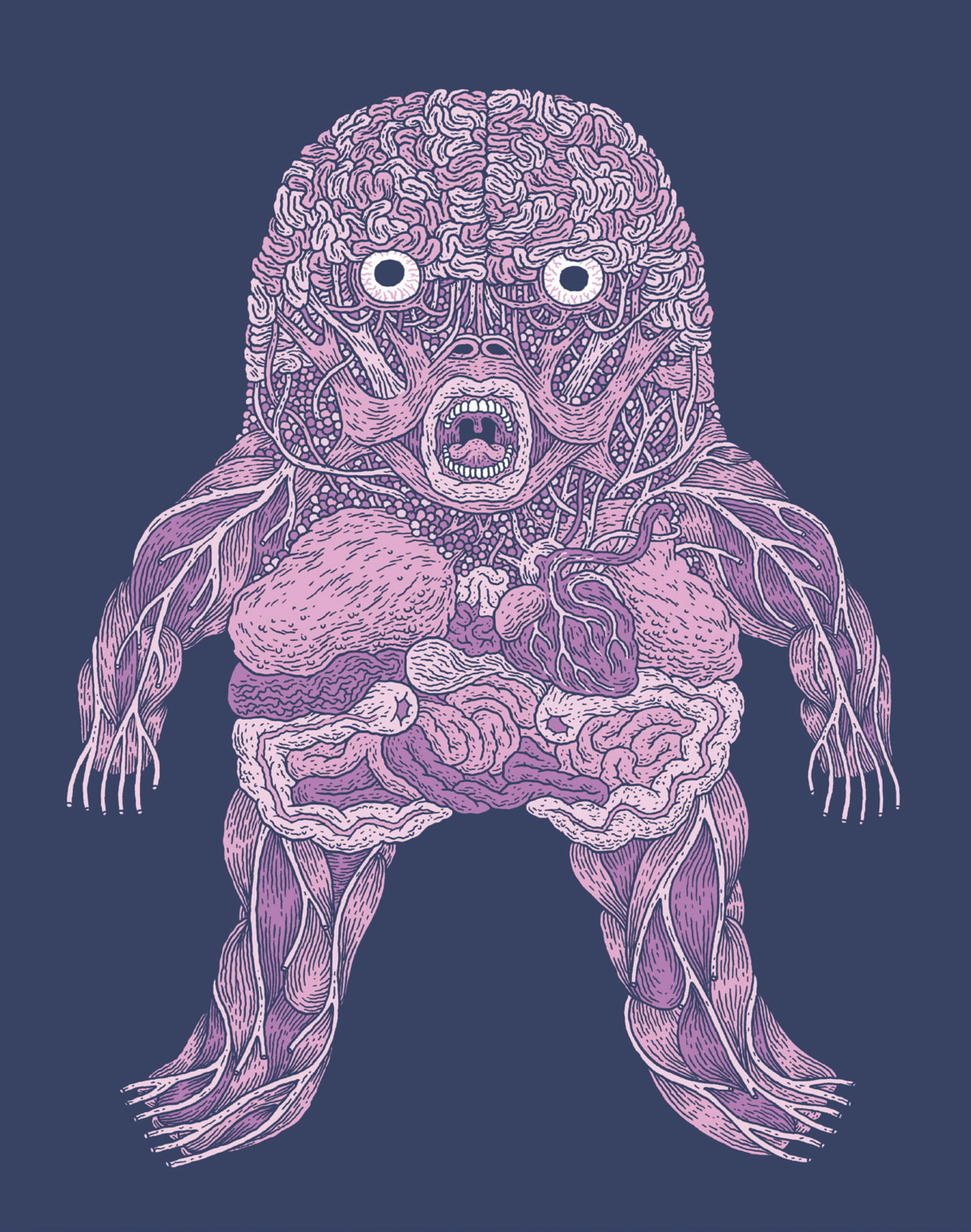

Ever get the feeling that your life, the universe, and everything are just a big cosmic snafu? That all the mesmerizing complexity of creation doesn’t make any more sense as you see the bigger picture? Anyone who’s ever pondered the meaning of existence through philosophy, religion, evolutionary theory, astrophysics, or reruns of Star Trek: The Next Generation will definitely enjoy By This Shall You Know Him.

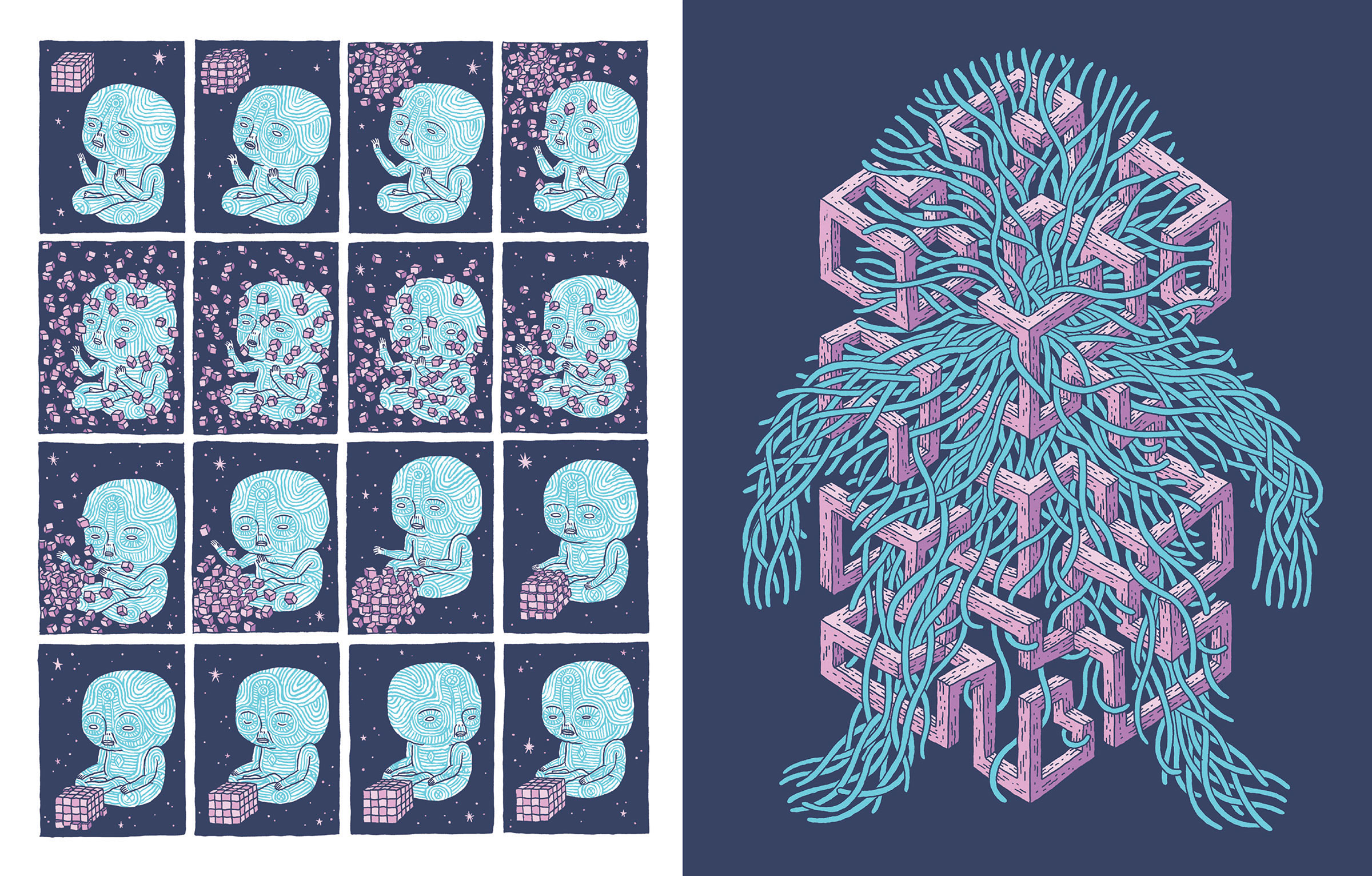

Written and drawn by the crazy-talented artist Jesse Jacobs, the story follows the birth of life, humanity, and good and evil, as the unintended side effects of a game of show and tell between squabbling, god-like celestial beings.

Much like his previous book Even The Giants, the story and art do double duty, at once profound, meditative, but also gross and funny.

Cleverly structured and beautifully rendered in 2-tone blue and purple, the larger book format really brings out the trippy detail in Jesse Jacobs’ artwork.

Q. Everything about this book is gargantuan! The story touches on everything from the nature of the cosmos, the origins of life and humanity, to the struggle between good and evil… Seems like you had a lot on your mind when you were writing this! You start the book with the Don Delillo quote “The spectacle of the unmattered atom.” What inspired this story?

Jesse Jacobs: I draw a lot of weird doodles on scraps of paper and in sketchbooks and I wanted to create a story that allowed me to freely showcase all of the random things that I most enjoy drawing. The idea of featuring characters that can conjure an infinite number of shapes and patterns and creatures meant that I could work pretty much anything I wanted to draw into the project. Initially I was intending to make more of an art book, with separate stand-alone drawings, but as the pages evolved I ended up working a lot of the random stuff together into a cohesive narrative. This comic is a collection of my drawings over the last year couched in a familiar creation-story.

My sketchbooks are full of a lot of my own writing along with stuff I hear on the radio, in podcasts, or read in books. When I was looking though it for ideas I saw that line about the unmattered atoms and drew it into the opening page. After a google search I saw I must have written it in there when I was reading Underworld, which I enjoyed all right but isn’t one of my top books or anything. I just think that line works really well with the overall sprawl of the story and imagery- just a bunch of weird stuff floating around.

Q. Lots of great creatures in this book! What are the 2-legged dog-like beasts called? Were they modelled after your dog?

Thanks. I really tried to balance the geometric shapes with looser more organic characters. Those dog guys were coming out a lot in my drawings. Where they came from and what they’re called I’m not exactly certain. I guess they’re just prehistoric dogs. I wish my dog had such strong hind legs as those guys. I did draw my dog in the comic but she’s really small and you wouldn’t know her to see her among all the other animals. I probably referenced Desmond when drawing those doggy creatures at some point, I’m sure.

Q. The tone of the title is fairly Judeo-Christian, but really the whole thing feels kind of Greco-Roman (where humans are the playthings of a rather dysfunctional family of very flawed celestial beings). Was it tricky blending the scienc-y perspective with the philosophical side of the story?

I won’t say some parts were not difficult, but the making of this comic was very enjoyable. Probably due to the lack of restrictions I had given myself. If a certain scene was becoming boring to draw, I would just move onto something else and return to it later. Like the blending of the animal and nature drawings with the geometric shapes and patterns, the story itself is kind of an assortment of a few approaches. The celestial beings are so different from the early humans that it was almost like drawing two different stories. Generally I had a lot of fun drawing all the stuff. I had the loose idea for the story, and from there the drawings guided much of it.

Q. 88 pages is huge! How long was the whole process of making this book end to end? (We feel like we saw some of the art for this a year ago at the last TCAF). Will you be taking a vacation, or are you already onto your next endeavour?

I started drawing it a little over a year ago, and you did see that screen print I did last year, featuring that weird wormy character encased in the chamber. That was one of the first images I made for the comic, and that thing pops up throughout the book. That character takes longer to draw than any other, and that says a lot because most of them took a long time. All the patterns on the beings are hand drawn, which was time-consuming but satisfying to do. I picture those blue patterns flowing and moving on their “skin”, kind of like Rorschach’s mask. So I guess it took me about a year to complete, though I had huge breaks where I did other stuff as well. There were times when the narrative kind of slid away and I edited a lot of pages out of the book that afterwards seemed unnecessary. Anne Koyama was a big asset in helping with the editing.

I’ve been thinking about and sketching another comic that is still in its early stages. I’ve also got a few other small projects on the go. It’s gardening season so we’re getting into that now. It’s always easier to be productive in the winter, I find. Koyama is bringing me to CAKE (Chicago Alternative Comics Expo) next month and I’m looking forward to that.

Q. The book will be launching this weekend at TCAF! What are you most looking forward to at this year’s event? What other Jesse Jacobs goodies can we snag at your table?

I’m really excited that Gabriella Giandelli will be in attendance, and I plan on catching her retrospective exhibit. I love her comics so much.

I wish I could say I had a bunch of stuff to sell, but this year I’m really just focusing on the book. I’m actually in the middle of doing some more skateboards with Homegrown, with imagery loosely based from By This Shall You Know Him. They will be finished for CAKE, and I’ll make sure to hang onto a print for you guys.

S&TM: Huge, huge thanks to Jesse Jacobs for taking the time to do this on the eve of TCAF!

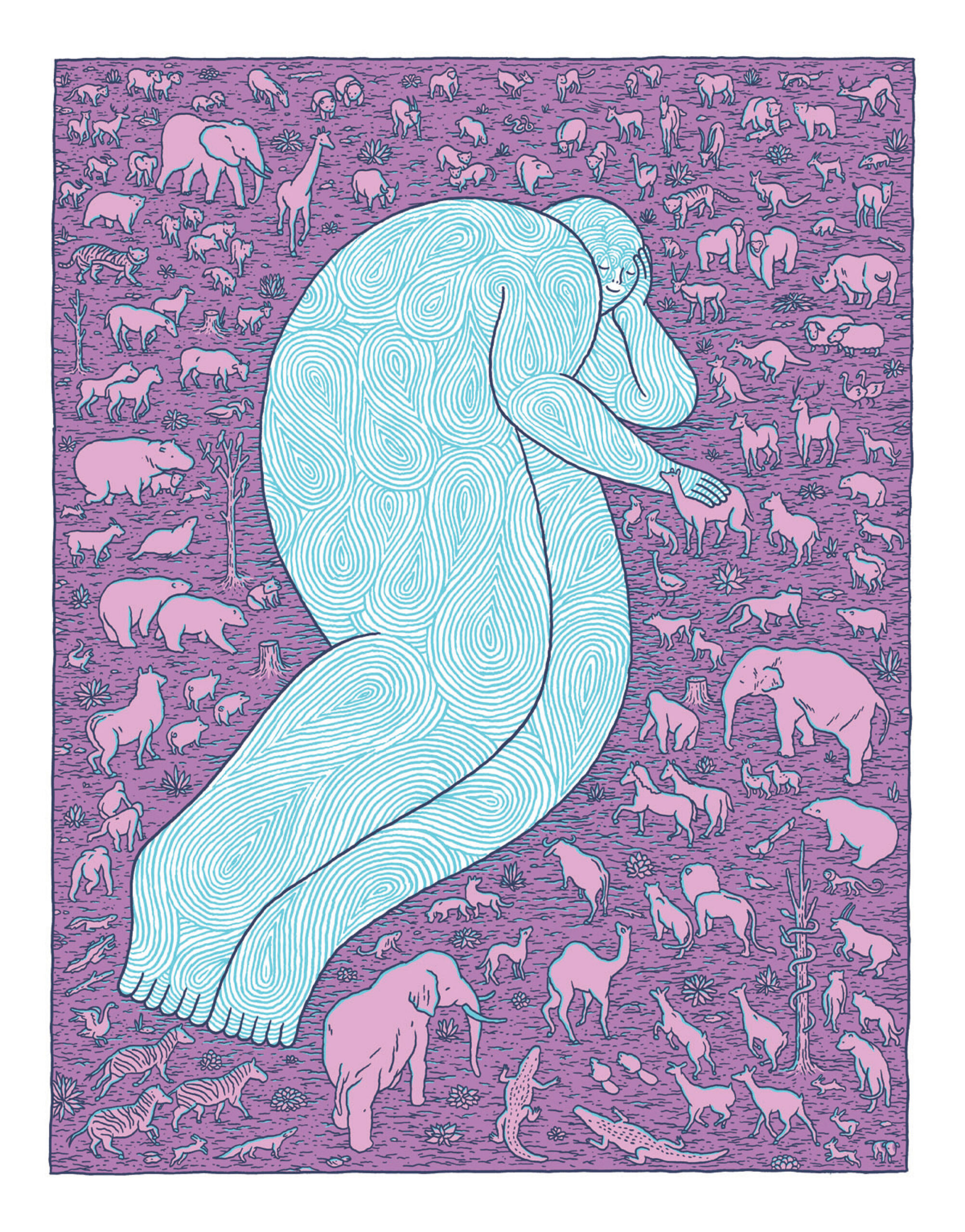

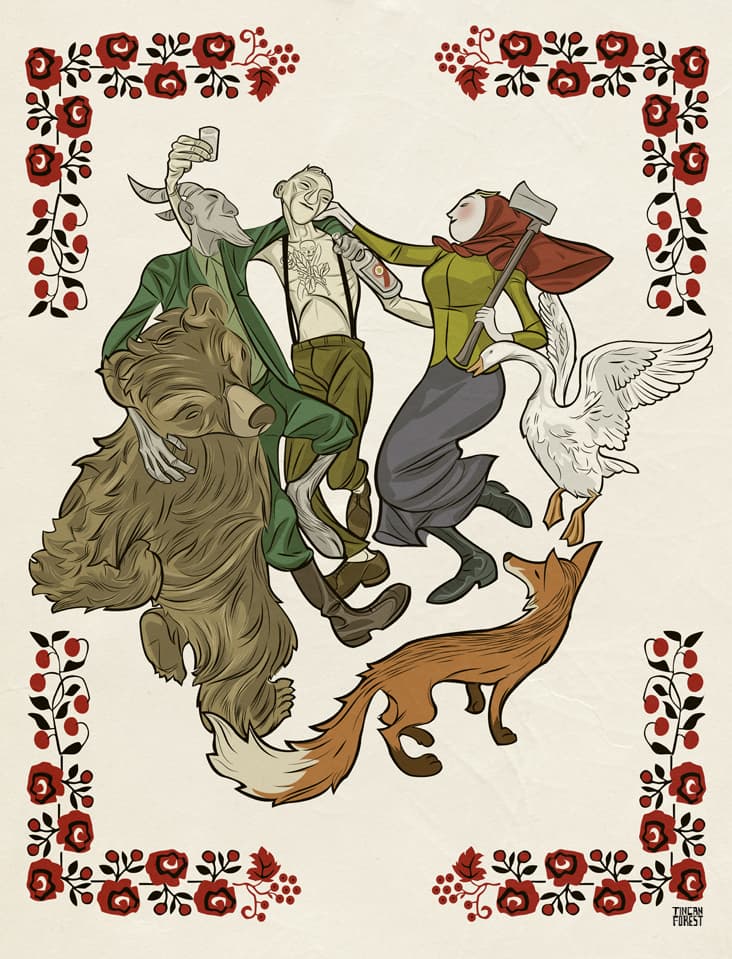

The deep, dark forest of our collective unconscious has never seemed more beautiful and mysterious than in the images of Tin Can Forest. The Toronto-based team of artists Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek spin tales where barter-happy demons and animal spirits, drawn from Slavic folklore, walk in step with witches and villagers. We caught up with Tin Can Forest to ask them about their work and new book “Baba Yaga and the Wolf” from Koyama Press.

Your bio mentions that you draw inspiration from the folk tales of your Ukrainian and Czech backgrounds. Could you tell us a bit about the characters and themes in your work?

Pat – I grew up second generation Ukrainian-Canadian in Winnipeg. The cultural traditions practised in our house hold were very much tied into the church, and growing up I couldn’t see Ukrainian culture as existing independently from the church. As an atheist and environmentalist, I was very happy to discover the pre-christian roots of traditional Ukrainian folk culture. It was a way “back into the fold”.

I feel the reverence humanity had for nature in pre-christian/pagan cultures is something that’s been lost in our contemporary society. Along with this shift away from living within the natural world, we’ve also forgotten a lot of traditional common knowledge, i.e. the names and properties of local flora and fauna. My work channels traditional Slavic rituals and symbols to celebrate nature.

Marek – I would say that my work is greatly informed by growing up in an immigrant household. We spoke Czech at home, I had a library of Czech storybooks and huge collection of Czech kids magazines that were full of whimsical comics strips; a style of comic that didn’t really have a parallel in the West. I was of course also really into American comics and animation, but the work of Czech artists like Josef Lada, Adolf Born, Jiří Trnka among others, were closest to my heart and are still a huge influence and inspiration to this day. As far as the characters I draw, it’s a set of archetypes, such as the devil, the baba yaga, the rusalka, the wolf, the bear, etc. that I keep reinterpreting and redesigning to explore different themes. The themes in my work have changed quite a bit over the years, from purely formal concerns, to personal and political narratives, and this cast of characters is like a visual vocabulary I use to explore the subject matter that interests me.

What does the name Tin Can Forest mean to you? How did you come to choose this as the name of your collaboration?

Pat – Marek came up with the name. It was a title of a poem he wrote for an art show we had in 2000. I thought it really suited us on several counts – the poem was written just before Y2K, and is about living in a dystopia of millennial anxiety and environmental disaster.

We love the forest, yet it’s constantly beleaguered by the detritus of modern consumer culture. At the same time Tin Can Forest has these nostalgic connotations to early comic strips, stop motion sets, fairy tales. I think the name expresses both our environmental politics, and describes our visual aesthetic as well.

Could you tell us a bit about your creative process and the way you work together as a team?

Pat – It depends on the project. Often when we collaborate on concepts and the development of ideas, I tend to do more of the research of themes and subjects we’re interested in, whereas Marek will compile the visual references.

Marek – Collaboration also involves long walks, fights, Eureka moments, dance parties, drinking binges, all night drawing or animating sessions, months of isolation on mountaintops, and loud music.

In addition to paintings and comics, Tin Can Forest designs, directs and produces animations both for client projects and personal work. Do you have a favourite from these activities? Do you approach personal and commercial work the same way?

Pat – We love to work on our own non-commercial projects the most, and this is our focus throughout the year. We are primarily artists who work commercially to support our art projects, though we’ve found working commercially is a good way to keep your skills in shape, and try new things you might not otherwise try.

Marek – Commercial work pays some of the bills. We’ve been lucky to work on a few really interesting commissioned projects, that offered a fair amount of creative freedom. We approach such jobs with the same enthusiasm as for our own art. On the other hand, there’s stuff we don’t want our work to support. We’re vegetarians, so to make animation or illustration for meat products would be hypocritical. I also think that car culture, especially in North America, has become way too overbearing, so we don’t want to help promote the car industry in any way.

We’re very excited about your forthcoming book “Baba Yaga and the Wolf”. Could you tell us a bit about this project and what we can expect?

Marek – Our new book is a kind of a hybrid between a comic and an illustrated story-book. It’s visually very much in the vein of our last book Pohadky, with a combination of my drawings and Pat’s decorative designs, but with speech balloons and text. The story of “Baba Yaga and the Wolf” is told by different narrators throughout the book, and is a riff on the classic ” bargain with the devil ” narrative. We spent the last winter living in the forest on an island in BC, some of the book was done there, and some was done in the Czech Republic, where we were this past spring. Both places greatly inspired the imagery in the book, so I would say it’s a Slavic folk tale set in a Canadian forest. The book is published by the mighty Koyama Press.

What can we look forward to from Tin Can Forest?

Pat – We’re working on a video and album design for Geoff Berner’s upcoming record “Victory Party”. We’ve been fans of Geoff Berner for years, and we’re very happy and honoured to be working with him.

We’re finishing a film we shot and animated in the forest on Salt Spring Island called “Heart of the Forest”. It features music by Wolves In The Throne Room.

We’re also doing a kids book with Kids Can Press based on our short animated film “Montrose Avenue”, which portrays a day in the life of our street here in T.O.

Keep an eye on our blog for updates on any other Tin Can Forest happenings.